When freedom is only available to those who can afford it, many end up paying with their lives.

By Nick Wing

Senior Viral Editor, The Huffington Post

|

| Of the nearly 750,000 inmates confined in jails around the U.S. at any time, between 60 and 70 percent haven’t been convicted. They are legally innocent. |

Jail deaths disproportionately impact poor defendants, according to a months-long investigation published by The Huffington Post this week, which documents more than 800 fatalities in the past year across the nation’s more than 3,000 city and local lockups. These facilities typically hold inmates who are awaiting trial or serving shorter sentences for misdemeanor offenses.

Our investigation also speaks to the issues jails face in caring for the people in their custody, many of whom stay incarcerated thanks in large part to a bail system that requires the accused to pay to get out of jail while they await their day in court. Most of the incidents we uncovered involved defendants who had not been found guilty of a crime, and were therefore legally innocent. They were only in jail because they couldn’t post bail.

Among those, we documented dozens of incidents where people died while facing low-level or nonviolent charges, like drug possession, traffic offenses or probation violations, which themselves may not have led to prison time. Many faced bail amounts ranging between a few hundred and few thousand dollars. In other cases, defendants were given high bail amounts for seemingly minor charges.

Sandra Bland, who died in custody a year ago this week, found herself in a similarly distressing situation after being arrested in Texas last summer, though she faced a more serious “assault” charge after being dragged out of her car and thrown on the ground by a police officer. Unable to pay her $5,000 bail ― or even a smaller percentage of that to cover a non-refundable bail bonds fee ― the 28-year-old black woman sat in a holding cell for days before allegedly hanging herself. If she’d have been wealthier, her fate might have been different.

Unfortunately, Bland’s inability to pay is not uncommon. There are nearly half a million inmates in jail who haven’t been convicted, according to the most recent federal data. Many are facing lesser charges, which suggests they are neither a threat to public safety nor likely to flee from justice. But because they don’t have money, they face immediate punishment and exposure to a potentially fatal form of pretrial confinement, all without due process.

Even when bail is not the difference between life and death, the process heavily disadvantages the poor and reinforces broader racial inequities in the judicial system. Critics say money bail violates the constitutional guarantee of equal access to justice, regardless of an individual’s wealth. And while a growing body of research suggests it is an expensive, inefficient tool that only contributes to high incarceration rates, it remains ubiquitous in courts across the country.

|

| The Waller County jail cell where Sandra Bland was found dead. If she could have afforded to bail out, she might not have been there. |

Cash Rules Everything

Up until the end of the 19th century, U.S. courts relied on a system of personal surety, which allowed the accused to be released without upfront payment, so long as they could find a person or entity to take responsibility for their return for trial. Payment was only required if a defendant didn’t appear.

As people became more transient around the turn of the century, communities became less tightly knit, making it harder to find willing sureties. Courts responded to this and other increasing flight risks by shifting to a system of secured bonds, in which payment must be delivered ahead of a person’s release. Bail became a question of a defendant’s immediate financial resources.

The change injected a huge influx of cash into the equation and brought about bail as we know it today. The commercial bail bonding industry, now legal only in the U.S. and the Philippines, followed shortly after, seizing the opportunity to make a tidy profit off those who could not otherwise afford their freedom. This sprawling industry handles about $14 billion in bonds each year, raking in $2 billion in annual revenue, according to a report by the Justice Policy Institute.

These businesses act as a surety for their clients, fronting money for their release in exchange for a non-refundable service fee ― usually a 10 percent premium on the total bail amount ― which can be paid off at a later time. After their release, defendants are typically subject to the order of the bail bondsmen, who are in turn responsible for making sure their clients return to court. If they don’t, these companies dispatch bounty hunters, who use a loosely defined set of powers to track down bail skippers.

Today, millions of people churn through U.S. jails each year, with the majority facing low-level charges. Defendants are disproportionately people of color, and the ones who remain incarcerated are often poor or suffering from mental health or substance abuse issues. Bail is not intended to be used to punish these individuals, and is not supposed to be set higher than is necessary to preserve public safety and assure that the accused returns to court. But many jurisdictions operate under ambiguous laws that allow them to assign bail without considering a defendant’s risk profile or ability to pay. This can lead to bail being set indiscriminately, often at arbitrary amounts.

To get out of jail under this system, defendants have to put up cash or other assets to pay a bond, which serves as collateral to secure their return for future court dates. If they show up, the court gives back their money upon the conclusion of the trial, regardless of the outcome. If they don’t, they forfeit the funds and face additional penalties for absconding.

This scheme benefits rich people. It allows many defendants with financial resources to post bond, bail out and go about their lives while they await trial, even when facing more serious charges.

Where this process favors the wealthy, it screws the poor. Those who can’t afford bail end up paying instead with time behind bars. Of the nearly 750,000 inmates confined in jails around the U.S. at any time, between 60 and 70 percent haven’t been convicted, according to federal data.

Taxpayers spend an estimated $9 billion each year to keep these innocent people under lock and key, all at the expense of other publicly funded programs, like education, transportation and infrastructure.

For those entangled in the system, the consequences can be brutal. Many indigent defendants are living paycheck-to-paycheck. If they can’t show up to work, they get fired and are stripped of the ability to be financially self-sufficient, or if they have dependents, are unable to support them. They may lose access to housing and benefits or fall short on payments, leaving them cut off from their families and other support systems. These pitfalls affect all defendants, regardless of their actual guilt, and only increase the odds of future incarceration.

“If you keep a low- or medium-risk person in jail pretrial, you are destabilizing them,” said Cherise Fanno Burdeen, executive director of the Pretrial Justice Institute, in an interview with HuffPost. “You are taking away from them the things that made them low-risk to begin with, and that will actually increase their likelihood of committing crime in the future. So we’re kind of biting off our nose to spite our face.”

There’s also the potential for more acute trauma during confinement, even for mentally stable inmates.

In some jails, cells are overcrowded, and inmates are exposed to violence, filth and disease; in others inmates can spend days in a bare cell without exercise, sunlight or human interaction. Inmates in one facility might have to drink water from a dirty spout located just above the toilet bowl, those in other jails may be forced to use “open pit toilets” that amount to little more than a foul-smelling hole in the ground. Jail officials can deny inmates access to basic necessities like toothpaste, soap and tampons and keep them in tiny rooms smeared with mucus, blood and feces.

Alec Karakatsanis of Equal Justice Under Law, an organization that has been challenging bail practices in jurisdictions across the country, said the public has become desensitized to the conditions imposed upon people who have been locked up without ever being found guilty of any wrongdoing.

“There’s absolutely no reason that these pretrial conditions have to be horrific, that’s just a policy choice that we’ve made for no reason,” Karakatsanis said.

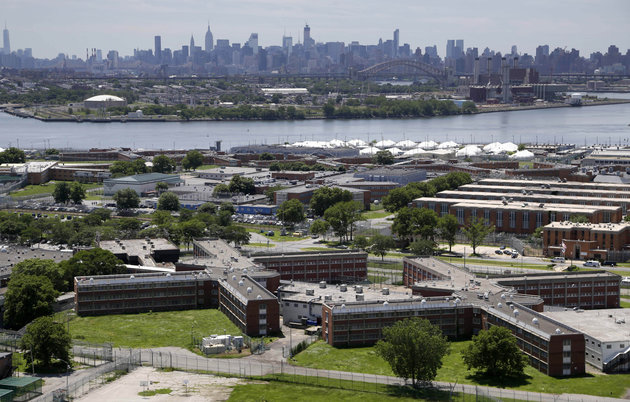

|

| The Rikers Island jail complex stands in New York City. Taxpayers spend an estimated $9 billion each year to keep innocent people locked up while they await trial. |

But Wait, It Gets Worse

The basic framework of our bail system today stands in opposition to the 1966 Bail Reform Act, a federal law that forbids keeping indigent defendants in jail before trial because they can’t pay (a later 1984 law allowed judges to consider danger to the community in setting pretrial release conditions). Years before the 1966 bill’s passage, then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy noted that “one factor determines whether a defendant stays in jail before he comes to trial. That factor is not guilt or innocence. It is not the nature of the crime. It is not the character of the defendant. That factor is, simply, money.”

More than half a century later, that dynamic remains largely unchanged outside federal courtrooms. While there have recently been a number of successful challenges to the system, the use of bail has only surged since the 1990s, according to the Pretrial Justice Institute, with 50 percent increases seen in both the dollar amounts of bonds and the number of crimes for which bail is set. Experts see the rise as part of an overly aggressive response to high levels of crime in the ‘90s, which led to the wider use of bail as a way to keep defendants locked up before trial.

This is a perversion of the judicial system, critics argue.

“Money or a failure to pay may not be the only reason why someone is incarcerated,” said Burdeen. “But that’s routinely disregarded in everyday courts across America.”

The average jail stay is 21 days, but pretrial incarceration can stretch on for months and sometimes much longer. Kalief Browder, a 22-year-old black man accused of stealing a backpack, spent three excruciating years in New York’s Rikers Island though he was never convicted of a crime. Prosecutors ultimately dropped the charges, but years later, Browder died by suicide. He was “unable to overcome his own pain and torment which emanated from his experiences in solitary confinement,” his family said.

Incarceration often pressures increasingly desperate defendants to make difficult choices. Some languish in jail for so long that they end up effectively serving the sentence for a charge before the trial is completed. In these cases, prosecutors may allow the accused to plead guilty and get credit for time served. While this may allow a defendant walk free, it can cost them a conviction for a crime they may not have committed.

These forces weigh heavily on people awaiting trial for lesser charges. Defendants in New York City were nine times more likely to plead guilty to a misdemeanor if they remained incarcerated ahead of court proceedings, according to 2013 data provided by Brooklyn Defender Services. And it’s harder to mount an effective defense behind bars. Just 38 percent of defendants who remained in jail pretrial had their cases resolved without a conviction, compared to 88 percent of defendants who made bail.

Bail has also been associated with broader negative effects on the outcome of criminal cases. A study of criminal data from Philadelphia between 2010 and 2015 found that defendants who were assigned money bail had a 6 percent higher probability of being convicted and a 4 percent higher probability of going on to commit another crime.

Some defendants have little choice but to turn to commercial bail bonds services to get out of jail. A failure to appear can leave defendants and their families on the hook for the entire bail amount. But even if they do everything right, these agreements often lead to large fees owed to privately owned enterprises.

Like many parts of the criminal justice system, these issues don’t cut equally across racial lines. Judges tend to favor whites over racial minorities in pretrial proceedings, according to research cited by the Sentencing Project. People of color, the poor and defendants with prior records are more likely to be considered public safety or flight risks, which influences decisions about whether to set bail and at what amount. When bail is set, blacks and Latinos are more likely than whites to face bond amounts that they cannot afford. A separate report by the Justice Policy Institute found that African Americans ages 18 through 29 receive significantly higher bail amounts than all other ethnic and racial groups.

|

| Commercial bail bonds services have turned innocent people’s pretrial release into an industry worth billions of dollar each year. |

How Do We Stop This Vicious Cycle?

As the public becomes aware of the fundamental injustices of the bail system, reform advocates are increasingly hopeful for change.

“People are starting to understand that this is not what we meant by getting tough on crime,” Burdeen said. “We wanted to get tough on violent crime, and what we’ve done instead ― or in addition ― is we’ve gotten tough on traffic tickets and driving on a suspended license and issues that are more along the lines of behavioral or health concerns, like trespassing or urinating in public.”

There are alternative approaches to pretrial release that aren’t solely contingent upon a person’s ability to pay. A growing number of jurisdictions are turning to individualized assessments that consider a defendant’s personal, financial and criminal background in order to inform bail decisions. These risk profiles can be used to determine appropriate bail amounts, as well as who must remain behind bars without bail, who can be released under the supervision of a pretrial services program and who can leave under their own recognizance.

Evidence suggests this system works. Not only does it limit the use of bail as a mechanism to keep communities safe and to get defendants to appear in court, but it does so at a fraction of the cost of the current cash bail scheme. Many people will show up for court with the help of simple reminders. Others need to be monitored more closely. And some truly aren’t fit to be out in the community while they await trial. These high-risk individuals often end up benefiting from the current cash bail scheme, because they’re able to take advantage of clumsy bond schedules and commercial bail bondsmen eager for business.

And with jail overcrowding now leading to significant problems around the country, reformers say it’s time to be more discerning about who gets locked up.

“Let’s not put anyone in jail unless we have a really good reason to believe that the only option we have left to us as a society is to take this person and put them in a cage,” Karakatsanis said. “That option, if exercised at all, should be exercised very, very rarely.”

Ryan J. Reilly contributed reporting.

No comments:

Post a Comment